Kubernetes Overview

Introduction

Kubernetes is an open source container orchestration platform that automates deployment, management and scaling of applications. Learn how Kubernetes enables cost-effective cloud native development.

What is Kubernetes?

Kubernetes—also known as ‘k8s’ or ‘kube’—is a container orchestration platform for scheduling and automating the deployment, management, and scaling of containerized applications.

Kubernetes was first developed by engineers at Google before being open sourced in 2014. It is a descendant of ‘Borg,’ a container orchestration platform used internally at Google. (Kubernetes is Greek for helmsman or pilot, hence the helm in the Kubernetes logo.)

Today, Kubernetes and the broader container ecosystem are maturing into a general-purpose computing platform and ecosystem that rivals—if not surpasses—virtual machines (VMs) as the basic building blocks of modern cloud infrastructure and applications. This ecosystem enables organizations to deliver a high-productivity Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) that addresses multiple infrastructure- and operations-related tasks and issues surrounding cloud native development so that development teams can focus solely on coding and innovation.

Predictable Demands Pattern

An application’s performance, efficiency, and behaviors are reliant upon it’s ability to have the appropriate allocation of resources. The Predictable Demands pattern is based on declaring the dependencies and resources needed by a given application. The scheduler will prioritize an application with a defined set of resources and dependencies since it can better manage the workload across nodes in the cluster. Each application has a different set of dependencies which we will touch on next.

Runtime Dependencies

One of the most common runtime dependency’s is the exposure of a container’s specific port through hostPort. Different applications can specify the same port through hostPort which reserves the port on each node in the cluster for the specific container. This declaration restricts multiple continers with the same hostPort to be deployed on the same nodes in the cluster and restricts the scale of pods to the number of nodes you have in the cluster.

Another runtime dependency is file storage for saving the application state. Kubernetes offers Pod-level storage utilities that are capable of surviving container restarts. Applications needing to read or write to these storage mechanisms will require nodes that is provided the type of volume required by the application. If there is no nodes available with the required volume type, then the pod will not be scheduled to be deployed at all.

A different kind of dependency is configurations. ConfigMaps are used by Kubernetes to strategically plan out how to consume it’s settings through either environment variables or the filesystem. Secrets are consumed the same was as a ConfigMap in Kubernetes. Secrets are a more secure way to distribute environment-specific configurations to containers within the pod.

Resource Profiles

Resource Profiles are definitions for the compute resources required for a container. Resources are categorized in two ways, compressible and incompressible. Compressible resources include resources that can be throttled such as CPU or network bandwidth. Incompressible represents resouces that can’t be throttled such as memory where there is no other way to release the allocated resource other than killing the container. The difference between compressible and incompressible is very important when it comes to planning the deployment of pods and containers since the resource allocation can be affected by the limits of each.

Every application needs to have a specified minimum and maximum amount of resources that are needed. The minimum amount is called “requests” and the maximum is the “limits”. The scheduler uses the requests to determine the assignment of pods to nodes ensuring that the node will have enough capacity to accommodate the pod and all of it’s containers required resources. An example of defined resource limits is below:

Different levels of Quality of Service (QoS) are offered based on the specified requests and limits.

.3 Quality of Service Levels Best Effort;; Lowest priority pod with no requests or limits set for it’s containers. These pods will be the first of any pods killed if resources run low. Burstable;; Limits and requests are defined but they are not equal. The pod will use the minimum amount of resources, but will consume more if needed up to the limit. If the needed resources become scarce then these pods will be killed if no Best Effort pods are left. Guaranteed;; Highest priority pods with an equal amount of requests and limits. These pods will be the last to be killed if resources run low and no Best Effort or Burstable pods are left.

Pod Priority

The priority of pods can be defined through a PriorityClass object. The PriorityClass object allows developers to indicate the importance of a pod relative to the other pods in the cluster. The higher the priority number then the higher the priority of the pod. The scheduler looks at a pods priorityClassName to populate the priority of new pods. As pods are being placed in the scheduling queue for deployment, the scheduler orders them from highest to lowest.

Another key feature for pod priority is the Preemption feature. The Preemption feature occurs when there are no nodes with enough capacity to place a pod. If this occurs the scheduler can preempt (remove) lower-priority Pods from nodes to free up resources and place Pods with higher priority. This effectively allows system administrators the ability to control which critical pods get top priority for resources in the cluster as well as controlling which critical workloads are able to be run on the cluster first. If a pod can not be scheduled due to constraints it will continue on with lower-priority nodes.

Pod Priority should be used with caution for this gives users the ability to control over the kubernetes scheduler and ability to place or kill pods that may interrupt the cluster’s critical functions. New pods with higher priority than others can quickly evict pods with lower priority that may be critical to a container’s performance. ResourceQuota and PodDisruptionBudget are two tools that help combat this from happening read more here.

Declarative Deployment Pattern

With a growing number of microservices, reliance on an updating process for the services has become ever more important. Upgrading services is usually accompanied with some downtime for users or an increase in resource usage. Both of these can lead to an error effecting the performance of the application making the release process a bottleneck.

A way to combat this issue in Kubernetes is through the use of Deployments. There are different approaches to the updating process that we will cover below. Any of these approaches can be put to use in order to save time for developers during their release cycles which can last from a few minutes to a few months.

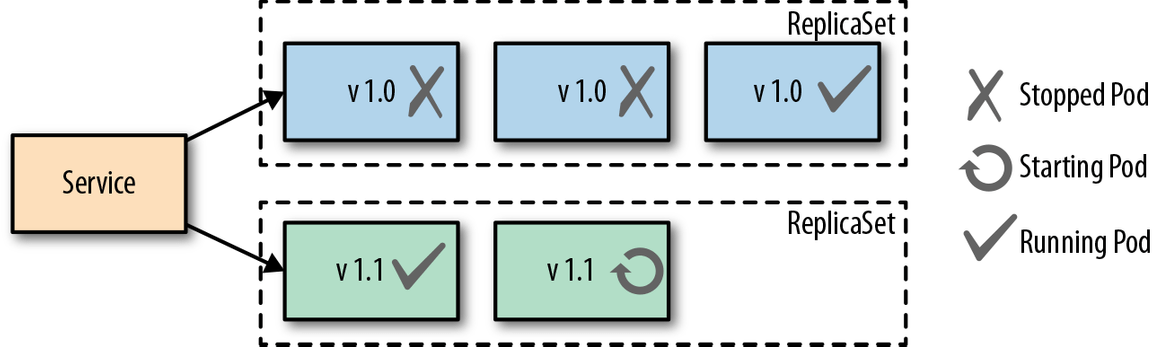

Rolling Deployment

A Rolling Deployment ensures that there is no downtime during the update process. Kubernetes creates a new ReplicaSet for the new version of the service to be rolled out. From there Kubernetes creates set of pods of the new version while leaving the old pods running. Once the new pods are all up and running they will replace the old pods and become the primary pods users access.

The upside to this approach is that there is no downtime and the deployment is handled by kubernetes through a deployment like the one below. The downside is with two sets of pods running at one time there is a higher usage of resources that may lead to performance issues for users.

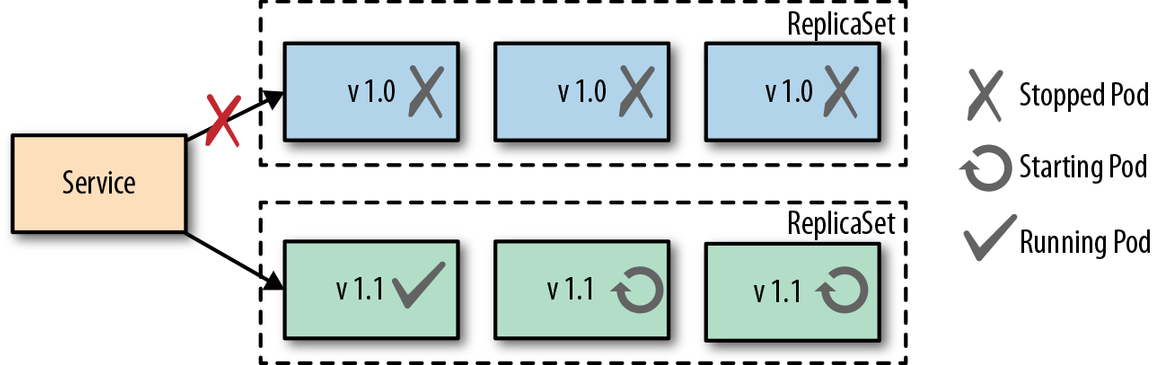

Fixed Deployment

A Fixed Deployment uses the Recreate strategy which sets the maxUnavailable setting to the number of declared replicas. This in effect starts the versions of the pods as the old versions are being killed. The starting and stopping of containers does create a little bit of downtime for customers while the starting and stopping is taking place, but the positive side is the users will only have to handle one version at a time.

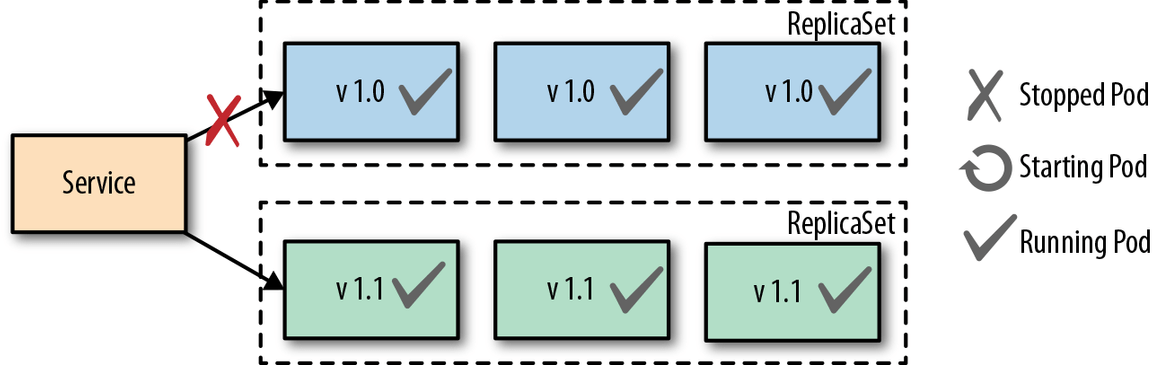

Blue-Green Release

A Blue-Green Release involves a manual process of creating a second deployment of pods with the newest version of the application running as well as keeping the old version of pods running in the cluster. Once the new pods are up and running properly the administrator shifts the traffic over to the new pods. Below is a diagram showing both versions up and running with the traffic going to the newer (green) pods.

The downfall to this approach is the use of resources with two separate groups of pods running at the same time which could cause performance issues or complications. However, the advantage of this approach is users only experience one version at a time and it’s easy to quickly switch back to the old version with no downtime if an issue arises with the newer version.

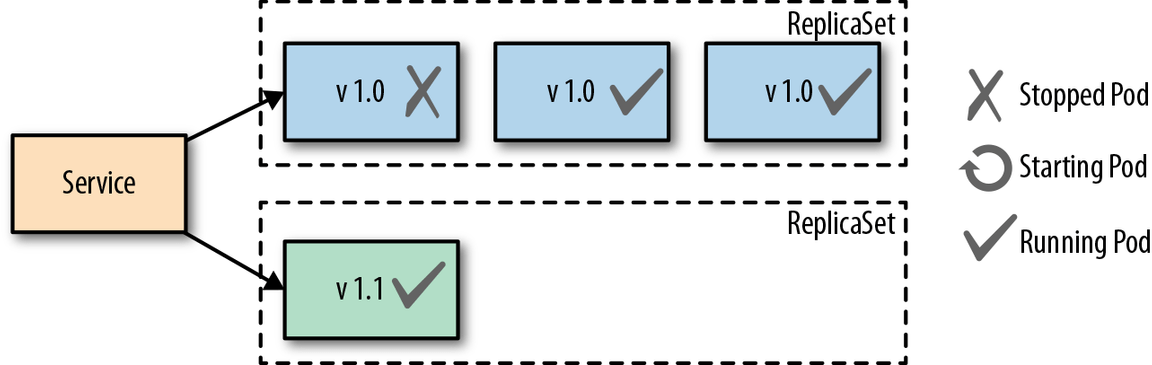

Canary Release

A Canary Release involves only standing up one pod of the new application code and shifting only a limited amount of new users traffic to that pod. This approach reduces the number of people exposed to the new service allowing the administrator to see how the new version is performing. Once the team feels comfortable with the performance of the new service then more pods can be stood up to replace the old pods. An advantage to this approach is no downtime with any of the services as the new service is being scaled.

Health Probe Pattern

The Health Probe pattern revolves the health of applications being communicated to Kubernetes. To be fully-automatable, cloud-applications must be highly observable in order for Kubernetes to know which applications are up and ready to receive traffic and which cannot. Kubernetes can use that information for traffic direction, self-healing, and to achieve the desired state of the application.

Process Health Checks

The simplest health check in kubernetes is the Process Health Check. Kubernetes simply probes the application’s processes to see if they are running or not. The process check tells kubernetes when a process for an application needs to be restarted or shut down in the case of a failure.

Liveness Probes

A Liveness Probe is performed by the Kubernetes Kubelet agent and asks the container to confirm it’s health. A simple process check can return that the container is healthy, but the container to users may not be performing correctly. The liveness probe addresses this issue but asking the container for its health from outside of the container itself. If a failure is found it may require that the container be restarted to get back to normal health. A liveness probe can perform the following actions to check health:

- HTTP GET and expects a success which is code 200-399.

- A TCP Socket Probe and expects a successful connection.

- A Exec Probe which executes a command and expects a successful exit code (0).

The action chosen to be performed for testing depends on the nature of the application and which action fits best. Always keep in mind that a failing health check results in a restart of the container from Kubernetes, so make sure the right health check is in place if the underlying issue can’t be fixed.

Readiness Probes

A Readiness Probe is very similar to a Liveness probe, but the resulting action to a failed Readiness probe is different. When a liveness probe fails the container is restarted and, in some scenarios, a simple restart won’t fix the issue, which is where a readiness probe comes in. A failed readiness probe won’t restart the container but will disconnect it from the traffic endpoint. Removing a container from traffic allows it to get up and running smoothly before being tossed into service unready to handle requests from users. Readiness probes give an application time to catch up and make itself ready again to handle more traffic versus shutting down completely and simply creating a new pod. In most cases, liveness and readiness probes are run together on the same application to make sure that the container has time to get up and running properly as well as stays healthy enough to handle the traffic.

Managed Lifecycle Pattern

The Managed Lifecycle pattern describes how containers need to adapt their lifecycles based on the events that are communicated from a managing platform such as Kubernetes. Containers do not have control of their own lifecycles. It’s the managing platforms that allow them to live or die, get traffic or have none, etc. This pattern covers how the different events can affect those lifecycle decisions.

SIGTERM

The SIGTERM is a signal that is sent from the managing platform to a container or pod that instructs the pod or container to shutdown or restart. This signal can be sent due to a failed liveness test or a failure inside the container. SIGKILL allows the container to cleaning and properly shut itself down versus SIGKILL, which we will get to next. Once received, the application will shutdown as quickly as it can, allowing other processes to stop properly and cleaning up other files. Each application will have a different shutdown time based on the tasks needed to be done.

SIGKILL

SIGKILL is a signal sent to a container or pod forcing it to shutdown. A SIGKILL is normally sent after the SIGTERM signal. There is a default 30 second grace period between the time that SIGTERM is sent to the application and SIGKILL is sent. The grace period can be adjusted for each pod using the .spec.terminationGracePeriodSeconds field. The overall goal for containerized applications should be aimed to have designed and implemented quick startup and shutdown operations.

postStart

The postStart hook is a command that is run after the creation of a container and begins asynchronously with the container’s primary process. PostStart is put in place in order to give the container time to warm up and check itself during startup. During the postStart loop the container will be labeled in “pending” mode in kubernetes while running through it’s initial processes. If the postStart function errors out it will do so with a nonzero exit code and the container process will be killed by Kubernetes. Careful planning must be done when deciding what logic goes into the postStart function because if it fails the container will also fail to start. Both postStart and preStop have two handler types that they run:

exec: Runs a command directly in the container.

httpGet: Executes an HTTP GET request against an opened port on the pod container.

preStop

The preStop hook is a call that blocks a container from terminating too quickly and makes sure the container has a graceful shutdown. The preStop call must finish before the container is deleted by the container runtime. The preStop signal does not stop the container from being deleted completely, it is only an alternative to a SIGTERM signal for a graceful shutdown.